Rightness and wrongness form a common source of argument and struggle. These relate closely to overts and withholds and the overt motivator sequence.

The effort to be right is the last conscious striving of an individual on the way out. “I-am-right-and-they-are-wrong” is the lowest concept that can be formulated by an unaware person.

What is right and what is wrong are not necessarily definable for everyone. These vary according to existing moral codes and disciplines and, before Scientology, despite their use in law as a test of “sanity,” had no basis in fact but only in opinion.

In Scientology a more precise definition arose. And the definition became as well the true definition of an overt act. An overt act is not just injuring someone or something: an overt act is an act of omission or commission which does the least good for the least number of people or areas of life, or the most harm to the greatest number of people or areas of life. This would include one’s family, one’s group or team and mankind as a whole.

Thus, a wrong action is wrong to the degree that it harms the greatest number. A right action is right to the degree that it benefits the greatest number.

Many people think that an action is an overt simply because it is destructive. To them all destructive actions or omissions are overt acts. This is not true. For an act of commission or omission to be an overt act it must harm the greater number of people and areas of life. A failure to destroy can be, therefore, an overt act. Assistance to something that would harm a greater number can also be an overt act.

An overt act is something that harms broadly. A beneficial act is something that helps broadly. It can be a beneficial act to harm something that would be harmful to many people and areas of life.

Harming everything and helping everything alike can be overt acts. Helping certain things and harming certain things alike can be beneficial acts.

The idea of not harming anything and helping everything are alike rather mad. It is doubtful if you would think helping enslavers was a beneficial action and equally doubtful if you would consider the destruction of a disease an overt act.

In the matter of being right or being wrong, a lot of muddy thinking can develop. There are no absolute rights or absolute wrongs. And being right does not consist of being unwilling to harm and being wrong does not consist only of not harming.

There is an irrationality about “being right” which not only throws out the validity of the legal test of sanity but also explains why some people do very wrong things and insist they are doing right.

The answer lies in an impulse, inborn in everyone, to try to be right. This is an insistence which rapidly becomes divorced from right action. And it is accompanied by an effort to make others wrong, as we see in hypercritical persons. A being who is apparently unconscious is still being right and making others wrong. It is the last criticism.

We have seen a “defensive person” explaining away the most flagrant wrongnesses. This is “justification” as well. Most explanations of conduct, no matter how far-fetched, seem perfectly right to the person making them since he or she is only asserting self-rightness and other-wrongness.

Scientists who are irrational cannot seem to get many theories. They do not because they are more interested in insisting on their own odd rightnesses than they are in finding truth. Thus, we get strange “scientific truths” from men who should know better. Truth is built by those who have the breadth and balance to see also where they’re wrong.

You have heard some very absurd arguments out among the crowd. Realize that the speaker was more interested in asserting his or her own rightness than in being right.

A thetan-the spiritual being, the person himself-tries to be right and fights being wrong. This is without regard to being right about something or to do actual right. It is an insistence which has no concern with a rightness of conduct.

One tries to be right always, right down to the last spark.

How, then, is one ever wrong?

It is this way:

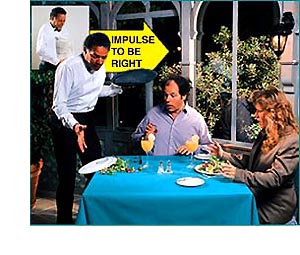

One does a wrong action, accidentally or through oversight. The wrongness of the action or inaction is then in conflict with one’s necessity to be right. So one then may continue and repeat the wrong action to prove it is right.

This is a fundamental of aberration (irrational thought or conduct). All wrong actions are the result of an error followed by an insistence on having been right. Instead of righting the error (which would involve being wrong) one insists the error was a right action and so repeats it.

As a being goes down scale, it is harder and harder to admit having been wrong. Nay, such an admission could well be disastrous to any remaining ability or sanity.

For rightness is the stuff of which survival is made. This is the trap from which man has seemingly been unable to extricate himself: overt piling upon overt, fueled by asserted rightness. There is, fortunately, a sure way out of this web, as we shall next see.

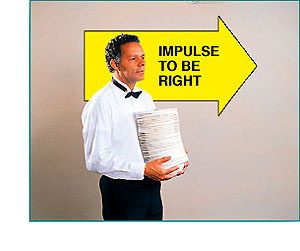

The impulse to be right lies within everyone.

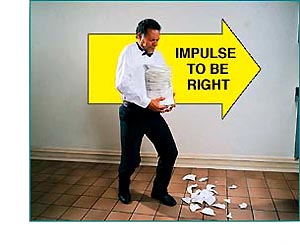

When a wrong action occurs, the person is thrown into conflict between his wrong action and impulse to be right. . .

. . . and he may continue to do the action in an effort to assert his rightness