In any activity in which people interact, moral codes are developed. This is true of any group of any size – a family, a team, a company, a nation, a race.

What is a moral code? It is a series of agreements to which a person has subscribed to guarantee the survival of a group.

Take, for example, the Constitution of the United States. This was an agreement made by the original thirteen states as to how they would conduct their affairs. Wherever that Constitution has been breached, the country is now in trouble. It first stated that there must not be any income tax. Later, that was violated. Then they changed another point in it, and another and another. And each time they have done this, it has caused problems.

Why are they in trouble? Because there are no agreements other than the basic agreement.

Man has learned that where he has agreed upon codes of conduct or what is proper, he survives, and where he has not agreed, he doesn’t survive. And so when people get together, they always draw up a long, large series of agreements on what is moral (that is, what will be contributive to survival) and what is immoral (what will be destructive of survival).

Moral, by these definitions, means those things which are considered to be, at any given time, survival characteristics. A survival action is a moral action. And those things are considered immoral which are considered contrasurvival.

When two or more persons have a mutual agreement, they act together – which we call coaction. Dancing with someone is a coaction; having a fight with someone is a coaction; working within an organization is coaction.

In naval experience, there is a known datum that a ship’s crew is not worth anything until they have braved some tremendous danger or fought together. You could have a ship sailing with a new crew and, even though they are trained for their duties, nothing works: the supplies never seem to get aboard, the fuel never seems to flow freely to the engines, nothing happens except a confusion. Then one day the ship meets a great storm, with huge, raging seas, and with every crew member aboard working together to bail the water out of the engine room and to keep the screws turning. Somehow or another they hold the ship together, and the storm abates (lessens, diminishes). Now, for some peculiar reason, we have a real ship.

Whether you have a group of two men in partnership or an entire nation which is being formed after the conquest of land from another race – it does not matter the size of the group – they enter into certain agreements. The longevity of the agreement does not have much to do with it. It could be an agreement for a day, an agreement for a month or an agreement for the next five hundred years.

People, then, in forming groups, create a series of agreements of what is right and what is wrong, what is moral and what is immoral, what is survival and what is nonsurvival. That is what is created. And then this disintegrates by transgressions (violations of agreements or laws). These transgressions, unspoken but nevertheless transgressions, by each group member gradually mount up to a disintegration.

In Scientology these transgressions and their effects have been examined in great detail. There are two parts which encompass the mechanism at work here.

A harmful act or a transgression against the moral code of a group is called an overt act. When a person does something that is contrary to the moral code he has agreed to, or when he omits to do something that he should have done per that moral code, he has committed an overt act. An overt act violates what was agreed upon.

An unspoken, unannounced transgression against a moral code by which the person is bound is called a withhold. A withhold is an overt act a person committed that he or she is not talking about. It is something a person believes that, if revealed, will endanger his self-preservation. Any withhold comes after an overt act. Thus, an overt act is something done; a withhold is an overt act withheld from another or others.

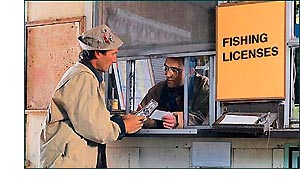

When a person agrees to follow a certain moral code . . .

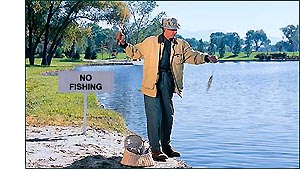

. . . but then violates those agreements, he commits what is called an overt act.

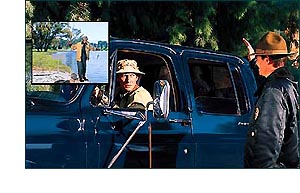

When a person does not communicate about something he has done for fear of the consequences, this is called a withhold.

The only person who can separate one from a group is himself, and the only mechanism he can do it through is withholding. He withholds transgressions against the moral code of the group from the other members of the group and therefore he individuates (separates) from the group, and the group therefore disintegrates.

The social ills of man are chiefly a composite of his personal difficulties. The workable approach is to help the individual handle his personal difficulties for the betterment of himself and the society of which he is a part.